I Remember the RERF | The Atomic Bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki 73 Years Gone

I visited the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) several years ago while doing some field work in Hiroshima. It’s a fascinating part of the history of Occupied Japan and one that’s not very well known. I presented a talk on this topic at the North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology/Toxicology History Society Annual Scientific Seminar in San Francisco a couple of years ago. I published a paper on my findings:

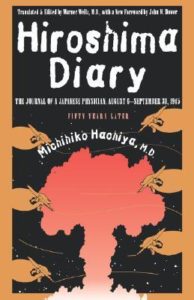

The grave is wide the Hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the legacy of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission and the Radiation Effects ResearchThe atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki created the largest sample of radiation-poisoned research subjects ever. The people that were affected by the bombs and radiation were named the HIBAKUSHA – literally, “the bomb-affected people.” The Americans realized that the Hibakusha were the most valuable research subjects in the world and quickly scrambled several scientific teams to examine the victims and gather biological samples. The Japanese science community had a head start, since they were on the ground and spoke the language, so literally within hours of the bombings, doctors began recording physiologic signs and symptoms from the patients they were desperately trying to help. These heroic physicians – many of whom were terribly burned and radiation poisoned themselves, courageously did whatever they could with absolutely nothing. There WAS nothing. No doctors or nurses, no medicine, no food, no shelter, no water. HIROSHIMA DIARY by Dr. Michihiko Hachiya is one of the best day-to-day, hour-to-hour record of the horror that was the first few days following the bombing of Hiroshima.

Dr. Hachiya wrote: “In two days I had become at home in this environment of chaos and despair. I felt lonely but it was an animal loneliness. I became part of the darkness of the night. There were no radios, no electric lights, not even a candle. The only light that came to me was reflected in the flickering shadows made by the burning city. The only sounds were the groans of the patients. What kind of bomb was it that had destroyed Hiroshima? Whatever it was, it did not make any sense.” The doctors were treating horrific burns and trauma and exposure to the best of their ability – but their patients suddenly started dying from a mysterious disease they had never encountered before.

On this day 73 years ago (August 9th, 2 days after the bombing)Dr. Hachiya wrote:”Regardless of the type of injury, nearly everyone had the same symptoms. All had a poor appetite, and over half had vomiting. Distinctly alarming was the appearance of blood in the stools of patients who earlier had only diarrhea. This morning other patients were beginning to show small subcutaneous hemorrhages and not a few were coughing and vomiting blood in addition to passing it in their stools. Among these patients there was not one with symptoms typical of anything we knew.”

Dr. Hachiya wrote of his patients; “Had these patients been burned or otherwise injured, we might have tried to stretch the logic of cause and effect and assume that their bizarre symptoms were related to injury, but so many patients appeared to have received no injury whatsoever that we were obliged to postulate an insult heretofore unknown.”

These remarkable men and women, working without laboratory reagents or equipment or food, water or even light, many of them, injured and sick and dying themselves, in a demoralized and abandoned and forgotten wasteland were able to reason it out. They formed a hypothesis regarding the degree of illness and proximity to the bomb blast based on their clinical observations and crude autopsies. When they were finally able to secure a microscope on August 20th, they began measuring blood counts and discovered agranulocytosis among many of the Hibakusha. They created a primitive epidemiologic map plotting blood cell count against proximity to the bomb blast. Incredibly, on August 26th, less than 3 weeks after being blown literally into the stone age, Dr. Michihiko Hachiya, the Director of the Hiroshima Communications Hospital, published the first official notice regarding radiation sickness. The night he posted this seminal document he wrote “I found it difficult to get to sleep because my bed was wet from the rain. Most of the night I spent slapping at mosquitoes.”

The Nobel prize winning novelist Oe Kenzaburo described the Hibakusha as “people who, despite all, didn’t commit suicide.”

Dr. Hachiya and his colleagues fought their own illness, hunger, thirst and fear to maintain life to the best of their ability while at the same time, serve their duty to history and collect data on the devastating effects of massive radiation exposure to humans.

Then the Americans showed up.

WWII had just ended. The Americans hated the Japanese. And the Japanese hated the Americans right back. The two groups of scientists and doctors were ordered to work with each other, but they could barely stand to look at each other. President Truman and Douglas McArthur ordered the Americans to work with the Japanese. The Japanese required the supplies and resources the Americans brought. This was the beginning of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC).

The Americans were ordered to cooperate with the Japanese. The Japanese cooperated out of necessity and a sense of obligation and responsibility to history.

The mission of the ABCC was primarily research and science but doctors performed health check-ups as part of the mission.

Many cultural missteps occurred in the ABCC – notice the linoleum tile floor – nearly impossible to walk on while wearing Japanese wooden shoes (geta)

The ABCC was 100% funded by the United States until 1975 when Japan began to contribute to the scientific and research mission and it became the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF). The legacy of the ABCC and the RERF is controversial. The organization published many important scientific breakthroughs but frequently was the target of vicious criticism from all sides. At its height of productivity, the RERF employed 1,600 people but only about 250 scientists work there now. The days of the RERF are probably numbered and its usefulness is about at an end, but it’s existence and work is an important and fascinating chapter of recent history.

Doctors and scientists at the RERF have studied the Hibakusha and published a lot of important research.